Walking into Madness: Nellie Bly’s Undercover Descent into a 19th-Century Asylum

A single step can change everything.

Imagine: it’s late 1887 in New York City. A woman named Elizabeth Cochrane (but soon to be known as Nellie Bly) heads toward “Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum.” She’s not sick, but she’s pretending to be. She’s going in as a patient to expose the hidden horrors within.

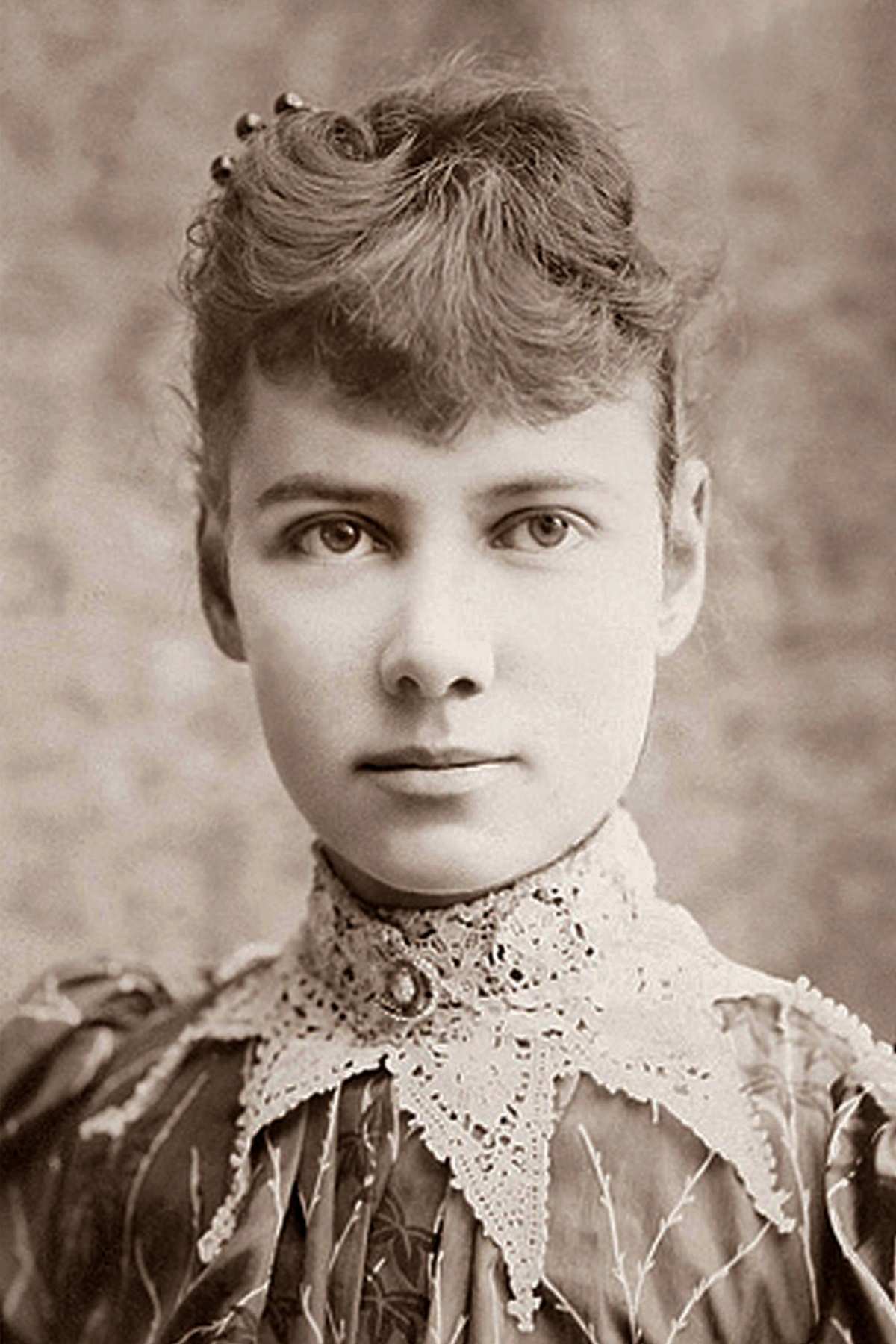

Who was Nellie Bly?

Born in 1864 in Pennsylvania, Nellie Bly was a restless spirit from the start.

In an era when most women were confined (figuratively and literally) to certain “acceptable” roles, Bly pushed boundaries. She became a journalist at a time when women were rarely taken seriously in that field, and she insisted on doing more than writing fluff pieces. She wanted the truth.

Her earlier exploits (writing under pseudonyms, tackling local injustices) built up her reputation. But Ten Days in a Mad-House would become her signature work — a bold, gritty piece of investigative journalism that changed how people thought about the mentally ill, about institutions, and about what a determined individual could do.

Deciding to go undercover: audacity or necessity?

You might ask: how do you convince a sane person to present herself as insane? Bly persuaded doctors and asylum officials that she was mentally disturbed. She prepared carefully:

- She studied behaviors that asylum doctors expected: muttering, acting erratic, perhaps making wild statements.

- She coached herself on appearance: messy hair, disheveled clothing, eyes wide, perhaps suspicious or wandering.

- She wrote her letters and affidavits convincingly.

But behind that disguise was a deeply serious motive: to shed light on abuses that the public would never see otherwise.

At that time, mental health was shrouded in stigma and secrecy. The sick weren’t always treated as human beings. Often, they were shunted out of sight.

“But here let me say one thing: From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted the crazier I was thought to be by all except one physician, whose kindness and gentle ways I shall not soon forget.”

~ Nellie Bly

Inside the asylum: a shock to the senses

Once admitted, Bly’s world narrowed to a suffocating maze of corridors, steel bars, barred windows, and hushed suffering. She chronicled:

- The stench: unwashed bodies, straw bedding, damp walls.

- The noise: distant moans, overlapping cries, footsteps echoing down long hallways.

- The light: dim or harsh, glare through bars, flickering lamps.

- The touch: coarse ropes, cold metal, rough sheets, bruised limbs.

She saw patients interacting in ways you wouldn’t expect: some subdued, others frantic, some barely responsive. Staff moved through this space as though it were simply another day, ignoring pleas, shoving patients, and punishing minor infractions.

Overcrowding was severe; women were packed together. Food was meager. Medicines were crude, sometimes harmful.

She later reported one horrifying rule: women could be punished for minor “misbehavior” by being locked in closets or cells for long hours. She saw staff neglect basic hygiene, or give patients little dignity or privacy.

Of course, not every staff member was cruel. Some showed faint kindness. But the system itself was so frayed, so underfunded, so indifferent, that humanity often got crushed in the cracks.

Science, medicine, and the ethics of mental health in the 19th century

In 1887, psychiatric science was in its infancy. Theories still hovered between mysticism and early biology.

Some believed mental illness stemmed from “imbalanced humors”, others considered “moral treatment” (a more humane approach), while nascent medical models were only then beginning to link brain pathology, heredity, and environment.

Institutions often claimed moral aims (remedying, reforming, restraining), but in practice, the underfunding, lack of oversight, and stigma warped those ideals.

Treatment could be brutal: physical restraints, forced baths, starvation diets, or sedatives of uncertain dosage.

Bly’s investigation challenged the dominant narratives. She forced readers (and the medical establishment) to ask: What is the responsibility of care? What dignity is owed to someone whose mind suffers? How do we test, monitor, and regulate institutions charged with holding the most vulnerable?

Her work bridged journalism and social medicine, pushing public health into realms it rarely ventured: mental institutions, prisons, and places shielded from scrutiny. For many women reading, her example was electric: she showed that truth-seeking doesn’t belong to men alone.

The explosive aftermath: Ten Days in a Mad-House and its ripple effects

When her article was published in The New York World in early 1888, the reaction was immediate. Readers gasped. Reformers rallied. Officials were forced to respond.

Her vivid storytelling (“I was lashed with a rope and flogged by attendants”, she wrote) sparked outrage. She described being starved, ridiculed, and dehumanized. The public could not ignore it.

Consequences included:

- Investigations: authorities inspected the asylum, discovering negligence.

- Reforms: budgets were increased, staff oversight improved, dietary and sanitary conditions addressed.

- Legal and policy pressure: changes were debated in city boards and state legislatures.

- Journalistic evolution: Bly’s work influenced future investigative reporting undercover work, exposés, and watchdog roles.

Still, change was not uniform or permanent. Resistance was fierce; some administrators claimed exaggeration or “sensitivity.” But the public had seen inside.

“I am happy to be able to state as a result of my visit to the asylum and the exposures consequent thereon, that the City of New York has appropriated $1,000,000 more per annum than ever before for the care of the insane. So, I have at least the satisfaction of knowing that the poor unfortunates will be the better cared for because of my work.”

~ Nellie Bly

Why Nellie Bly’s story still matters

At first glance, Nellie Bly’s exploit seems historical. But it pulses with relevance for anyone tuned into mind, body, environment, and justice:

- Mental health as biological and environmental: We now understand that brain chemistry, trauma, stress, and environment shape mental health. Bly’s story reminds us that institutions must reflect that complexity.

- Accountability in care systems: Hospitals, psychiatric wards, nursing homes — they all can slip into neglect unless watchdogs exist. Her work is a case study in institutional transparency.

- The courage of observation: Science and journalism share a calling: observe, record, question. Bly merged them.

- Human dignity: Even in the worst conditions, Bly observed small acts of grace, voices, lives. That resonates for anyone who cares about wellbeing, health equity, and recognizing marginalized humanity.

When she walked into the asylum, she carried more than pen and notebook — she carried empathy, daring, accountability.